I have been interested in books, TV shows and lately Podcasts about supernatural, paranormal, extraterrestrial and other such stuff for a long time. Lately I have been listening to lots (lots) of Podcasts dealing with all sorts of topics somewhat from the fringe. Sometimes the host(s) of the show and the guest are very careful how they talk about a subject. Often, though, words (or memes) such as reincarnation, near-death-experience, ghost, alien, UFO, etc, are dropped as if they (and we, the listener) know exactly what that is. The guest sometimes talks about the afterlife in such specific ways as if they had just finished a college course on it. Of course that kind of language usage and specific words and terms dominate our daily life. Terms, such as food, sleep, super market are spoken and used in written form and usually they are understood close to what they were intended to mean.

Quickly, though, we come to more dubious words that are used in everyday language by a large number of people and on the surface we go: “Sure, I know what a conservative (or liberal, or progressive) is.” Except, that you have two different people trying to explain it and their understanding will most likely not overlap much. How about the word god? How about the phrase “I believe in god?” What does that mean? This could conceivably take a lifetime to explain – and the explanation would again contain usage of terms that are assumed to convey clear, unambiguous information but in turn require more explanation.

In a way, isn’t this what the working body of science has tried to mend? When ‘normal’ people talk about a theory they usually mean something they think is an explanation – not necessarily backed by any evidence or any logical or rational path of reasoning. In science the word theory has a very specific meaning and is clearly defined. It seems science strives to implement very strict definitions of the language and terminology it uses. That means, ideally, that those who have studied specific scientific fields can communicate in very precise and unambiguous terms. While this is the ideal situation, more often than not it has turned out that established scientific fact (along with the terminology) was simply wrong. Luckily, science can admit errors and correct them

Now we get to the fringey stuff, where two folks talk about reincarnation or ghosts as if they both knew exactly what is being talked about, assuming that they are also talking about the same thing, and (before I forget) that those things actually exist. Can there even be a meaningful discussion under such circumstances? Again: the thing that is being discussed is most likely not the same for each party, often one or both of the parties have not experienced anything like a ghost personally but get their information from other sources, who also use terms and words which are not defined but are taken as truth. This is how huge pyramids of fringe theories are built on hot air.

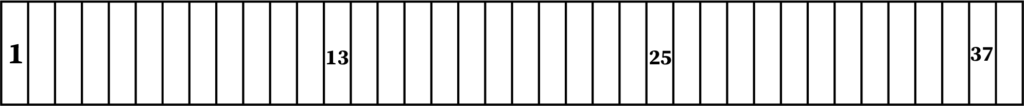

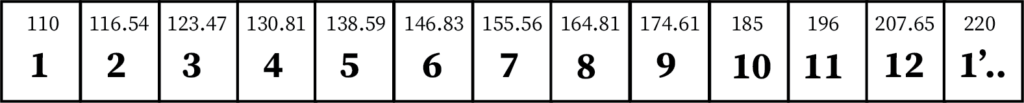

You could claim that much of the scientific body of work and knowledge is equally built on hot air. Perhaps it is, I don’t care, but the rigorous definition of terms and relationships plus a high internal consistency amounts to something and has changed material reality. It’s akin to a bunch of musicians knowing the same tune in the same key, agreeing on how to start, when to modulate to where and how to end. It may all be made up from hot air, but it works. While you put a bunch of people together, some who may not know how to hold their instrument, you tell them to play a tune that everybody should know from listening to the radio, nobody counts off, nobody knows the key (or even what a key is). What you’ll hear could be very adventurous, maybe interesting but probably won’t resemble the song they were supposed to play. And if they try it again it will sound totally different.

I guess here comes the clincher. Is it possible that nothing has any meaning unless it is given meaning by what or who consciously experiences it? And then that experience will be incredibly deep, valuable and detailed until the experiencer tries to explain it to someone who hasn’t experienced exactly the same thing – at which point the experiencer will start accepting the verbalized, official version him or herself. Makes you wish for something like telepathy, where an experiencer could transmit the experience directly to somebody else….

Some podcasts I really like (warts and all):

Skeptiko

Mysterious Universe

Paranormal Podcast

The Paracast

and on the skeptical side:

The Skeptics Guide to the Universe

Geologic Podcast

Big Picture Science

Skepticality

There are of course a lot more but the day is only so long….